2.12.2026

Granola's Big Bet on Gravity

The last twenty years of value creation in technology has been based on the height and resilience of walls.

Apple's blue bubble moat — its shared context across phone, laptop, iPad, and television. Google's ability to be everywhere for everyone — email, calendar, documents, spreadsheets, your entire identity as a quilt of your search terms. Meta bought all that it could not clone; if people are connecting with each other today, they're very likely doing so on a platform Zuck owns. Amazon sells everything. Everything.

Last week, Granola launched an MCP server.

For those who have heard that term but aren't entirely sure how to use it in a sentence (no judgment here, trust me), MCP stands for Model Context Protocol. It's an open standard that lets AI applications plug into tools and data in a consistent way. Said differently, it's an intentional hole in the wall, where information and data can be passed back and forth.

Without trying to sound too hyperbolic, this is a big fucking deal.

We've said before (and will continue saying, obviously) that the value of the foundation models themselves (closed, open or otherwise?) is enormous but also commoditizing rapidly. Models have a monetary moat, but are otherwise built on concepts. Concepts can be copied. We learned that lesson when DeepSeek launched not too long ago.

Meanwhile, products that touch the actual user (application layer products) are accruing more and more value, for a couple of reasons:

1. These products can serve utility in a much more precise and targeted way than a generalist model and, thus, build up more brand affinity and user love. They can be tuned and interfaced as sharp tools vs. blunt instruments.

2. Because they have reliable high frequency use, these products are soaking up proprietary context and data from their users that generates even more stickiness and increases switching costs. (For example, I am in the top .02 percent of Granola users. That amount of context means that this product is increasingly becoming the operating system of my life, and not just my work.)

Stickiness is just another word for a wall.

One wouldn't be judged for believing that Granola's most defensible asset is its data; that thousands of my conversations live within the four walls of its application and can't be passed along to Gemini or Claude or ChatGPT. Believing that, you might nervously scratch your head at why Granola would drill a big ol' hole in one of those walls.

The answer is thrilling — and not just because we're investors in Granola. It's thrilling because we're human beings who live in 2026 and, to be honest, something's gotta give.

The hole in Granola's wall exists because the next 20 years of value creation in technology will *not be based on the height of walls*, but rather on *gravity*.

Chris and Sam have correctly identified that the most defensible thing about their product is NOT that they hold all the context of my meetings. Rather, it's that Granola is an agnostic tool that is first and foremost loyal to me.

Granola is with me no matter where I'm having a conversation — Google, Zoom, in person.

Granola knows who I am, understands my goals, and is able to process notes in a way that is singularly unique to my own agenda. For example, when I'm in a conversation with one of our LPs, my Granola notes never show me anything I've said about Betaworks. I am, after all, the one who delivered that information in the first place; it's stuff that I already know. Instead, the notes show me what questions the LP has asked me, the latest updates on their business, and any follow-ups I've promised to deliver. Their Granola notes from the same meeting would be wildly different from mine. And that's the beauty of it!

Of course, part of what makes that possible is the context of my existing conversations within Granola. There is meaningful value there that I don’t mean to discredit. However, this foundation of data and positioning of the company frees the team up to focus monomaniacally on creating the most comprehensive and high quality AI system for conversational data in the world — determining the relationships of those having the conversation, the purpose of the meeting, and the best possible output for each individual and impacts to their business beyond that. That insight, that technical feat, does not leak out through the hole in the wall. It's gravitational.

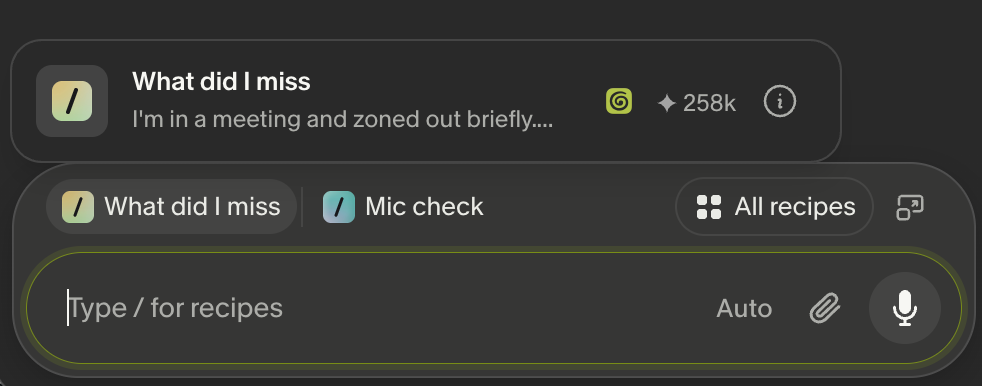

The thing that perhaps inspires the most loyalty is the mighty Recipe. There are many available (mostly created by power users like myself); Granola has given each user the right to create their very own, tailored to whatever specific workflow makes the most sense to them. The one that I would wager gets the most use, however, is "/what did I miss?".

I hate to reveal this secret but I push that button probably a dozen times a day. It has saved me more times than I care to share. It's a black hole's worth of emotional gravity that pulls me back to Granola, over and over. As this user describes it: “Granola built semantic intelligence into the protocol layer.”

We're entering a buyer's market, ushered in by Claude Code and Cowork, with OpenClaw (formerly ClawdBot and, if only for a moment, Moltbot) in tow – Cursor deeply in the rearview mirror and Codex vying for attention.

These products are perhaps still a touch too technical for normies, but they are a sure sign of what's to come. They are a harbinger of hyper personalization informed by context graphs, of democratized access to software, and of an empowered individual user.

As the AI wave continues to compound and build, no crest yet in sight, moats won't be engineered — they'll be earned.

Switching costs are imposed by sellers in the form of data formats, integrations, contracts, and retraining. *Leaving* costs, by contrast, are imposed by the buyer on themselves. When a product works well, I use it more. It, in turn, becomes even better, and even more integrated into my workflows. The moat is emotion; the moat is appreciation; the moat is learned behaviors burned into the neurons of human brains. The moat is earned.

I understand the trepidation that might come from this paradigm shift in the world of venture. It's similar to the fear that has investors slow to wean themselves off of the tried and true SaaS investment cycle with its familiar dynamics, margins, and multiples. Early signs would suggest that in the era of AI, building systemically integrated businesses (even those that might look superficially like services businesses) is the best and fastest way to replace or create an industry, rather than sell a tool to an industry. (As a reminder, these kinds of companies are exactly what we're looking for in our upcoming Agent Systems Camp.)

Change can be hard.

But the insight that we have at Betaworks is: earned stickiness is actually much more valuable than forced stickiness. Users don't resent it, they evangelize it. They feel passionate about it; like the product is theirs, not the other way around. Take Granola's recent rebrand as an example; love it or hate it, it elicited a reaction that was heard deep and wide on Twitter and beyond. That's because people feel something deeply about Granola itself, and the technology is allowing companies to create that feeling more powerfully than ever before.

In the buyer's market, paradoxically, giving users freedom is precisely what will make them stay.

Granola isn't the only company in our portfolio that's on this path. It's a core principle of our own thesis and has been for some time.

HuggingFace is perhaps the best and biggest example of an open, neutral entity in the entire AI ecosystem.

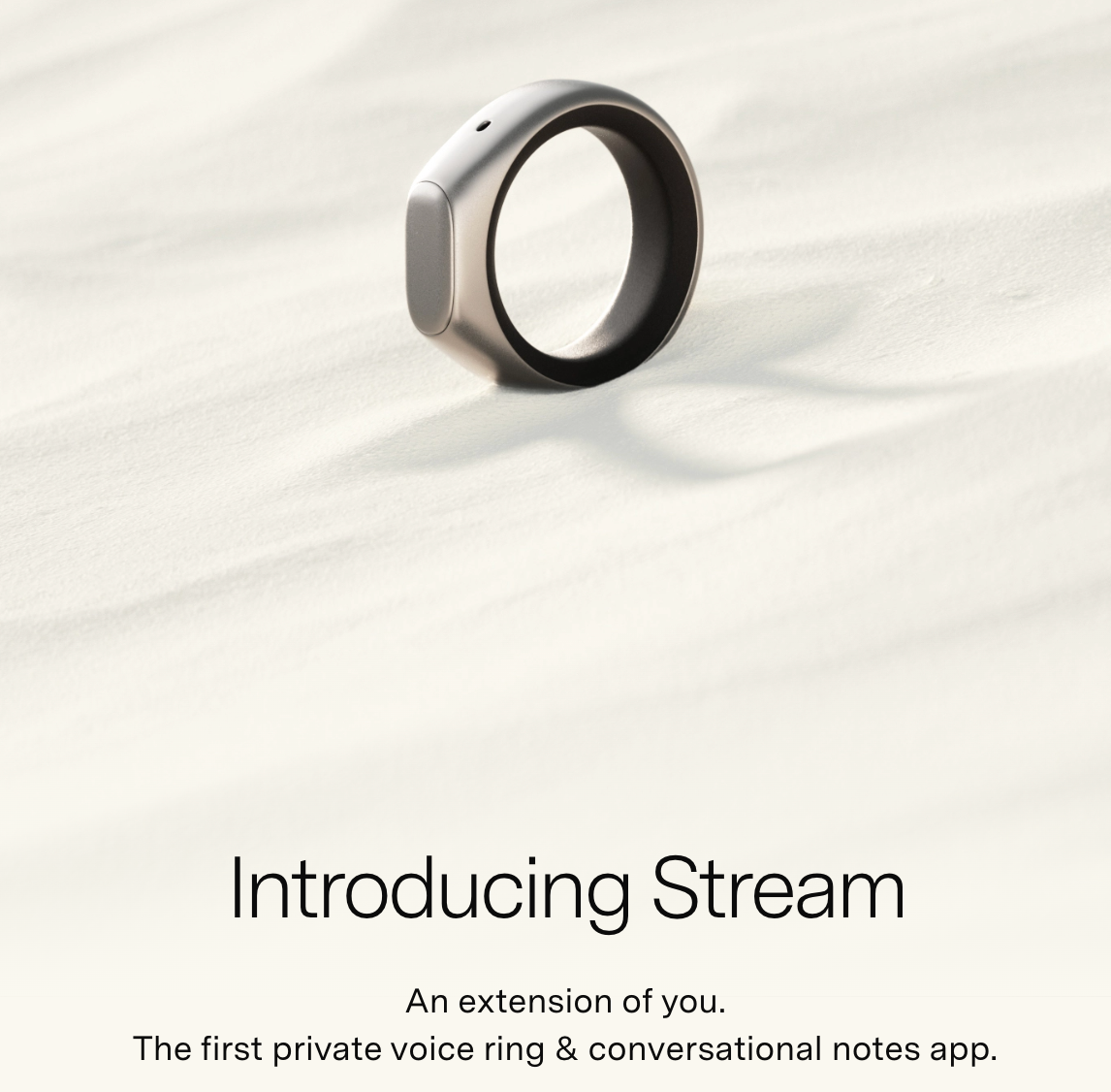

Sandbar already understands the importance of allowing for flexible and open customization. We sat down with Mina Fahmi at our AGM last week where he demo'd, for the very first time, web search via the Stream Ring. This is the tip of the iceberg. Sandbar is building to be the next hardware interface for AI, which necessitates the ability to interact with all types of software, whether it was developed by Sandbar or not. The company's ability to win will not be based on trapping you, and every conversation you've had with the software, inside its application. It will be based on whether or not it delivers on its core promise: to be an extension of you. Gravity.

Plastic Labs has developed a reasoning model called Neuromancer that powers its Honcho memory management system. (You've obviously heard us talk until we're blue in the face about the wild and rousing explorations of context and memory in AI, and this team may be taking the most riveting approach yet. You can read more about it here.) Neuromancer treats memory as a reasoning problem, rather than a storage and retrieval problem, which is much like the way the human brain treats memory, but without the same compute limitations.

Plastic Labs understands how strategic memory is -- that applications will want to own their context moats without forking it over to the foundation models. They also understand that users who are being given a taste of AI that is loyal to them (ahem, Granola) will demand that all other AI is an extension of their own mind, steered by themselves or a representation of themselves that is loyal and true.

Twin and Dessn are doing similar work. Handing the keys to the kingdom back to users, ensuring that the context with which they're executing is owned and operated by the user.

I may be wandering off and perhaps diving into a layer of this concept that's a bit too technical, but you'd forgive my enthusiasm. We've invested in a portfolio of companies that 'get it'. And 'it' is finally revealing itself in a way that can't be ignored.

Take the Super Bowl ads from Anthropic. A bit exaggerated, but highly resonant, to the point where they elicited a public 500-word response from Sam Altman. His response, despite perhaps coming across as a whiny shot to his own foot, makes an important point about democratizing access to AI. It still misses, though, where it really counts.

It has taken us (humans, I mean) long enough, but we have learned that we (and our attention) cannot be the product. Our data cannot be the product. The product must serve the human, or it will be replaced with one that does. Keeping someone as a user — and having them recommend your product to friends, or bring them into the companies they join — becomes a matter of love, not lock-in.

There is some irony in the fact that the greatest technological shift of our lifetime — one that seemed to be squarely in the hands of one (or maybe two) companies — is actually the very thing that splinters the power back out into the hands of the people.

We welcome a buyer's market, where stickiness is earned and not engineered, and where the next 20 years worth of value will be based on gravity rather than entrapment.